On the Ambuguities of Sorry

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the modern cultural landscape, few phrases are as scrutinized, debated, and often dismissed as the public apology. When a public figure faces backlash, warranted or not, the inevitable “sorry” statement often follows. Yet, these pronouncements frequently ring hollow, sounding more like carefully crafted PR than genuine contrition. This pervasive sense of inauthenticity highlights a deeper issue: the inherent ambiguity embedded within the word “sorry” itself. This ambiguity transforms apologies into a societal Rorschach test, fueling division and tribalism, and underscores a critical need for greater clarity in our language and interactions.

The Problem of Ambiguity and Cultural Division

The problem begins with the ambiguous nature of the apology, particularly in the public sphere. When a sorry is issued, its true meaning and sincerity become subject to individual interpretation. This ambiguity serves as a Rorschach test, upon which each observer projects their own biases, expectations, and judgments. The lack of a clear, shared understanding of the apology’s intent inevitably leads to division. People not only rush to judge the initial action but also secondarily judge those who interpret the apology or the situation differently. This creates fertile ground for tribalism, where groups form based on shared conclusions, often demonizing those who arrive at opposing viewpoints. Defending someone accused of wrongdoing can even lead to being accused of adopting their perceived flaws or beliefs, further calcifying divisions and hindering empathetic understanding.

Deconstructing the Word “Sorry”: Multiple Meanings

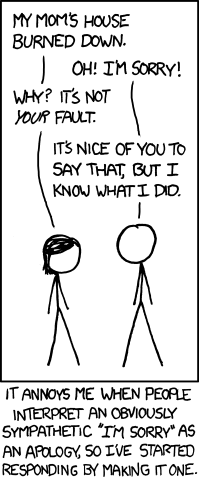

A significant source of this confusion lies in the fact that the single word “sorry” can simultaneously convey several distinct messages. We commonly use “sorry” in at least three different ways, and conflating these meanings is a primary driver of misunderstanding. The first meaning is offering sympathy. This is perhaps the simplest form, expressing sadness or concern for another’s misfortune, as in the classic XKCD comic above where one character says their mom’s house burned down. This character is merely expressing sympathy, but it is being interpreted as admitting guilt or wrongdoing. When we say “I’m sorry” in this sense, we are accepting responsibility for a harmful action, implicitly acknowledging that something wrong was done and, often, that some form of restitution or consequence is necessary to “make things right.” This is frequently the meaning the public demands from a figure who has erred. The third meaning is expressing regret – conveying a wish that a past action had not occurred. While regret is often a natural consequence of believing one has done something wrong, the expression of regret itself doesn’t automatically constitute an admission of fault or acceptance of consequences to others. The difficulty arises because these three meanings are not mutually exclusive; a single “sorry” could potentially encompass one, two, or all three, leaving the listener uncertain of the speaker’s true intent.

A Historical Side Note on “Apology”

Interestingly, another term that we often use interchangeably with “sorry” carries its own historical baggage. Apology. The word derives from the Ancient Greek “apologia,” which meant a formal defense or justification of one’s actions, beliefs, or character. Socrates’ famous Apology is not a statement of regret, nor is it an admission of guilt. Really, it is a reasoned defense against accusations. Over centuries, the meaning of “apology” shifted dramatically in English. Today, to “apologize” means almost exclusively to express regret and admit fault or wrongdoing. This just further shows how ambiguities in this area are not new.

Why Ambiguity Persists in Public Apologies

Given the potential for misinterpretation and the high stakes involved, particularly for public figures, ambiguity in apologies often persists not by accident, but by design. There exists a fundamental tension between the public’s demand for accountability and admission of guilt, and the individual’s natural desire to avoid negative consequences, whether legal, social, or professional. This tension creates a powerful incentive for strategic ambiguity. Public figures may issue apologies that are intentionally vague, designed to sound remorseful enough to appease critics and alleviate pressure, while simultaneously avoiding a clear admission of guilt that could lead to tangible repercussions. This pursuit of “plausible deniability”—the ability to later claim their apology meant something other than accepting fault—is a primary reason why so many apologies feel disingenuous. It’s a negotiation between appearing contrite and avoiding consequences, and the resulting language is often deliberately fuzzy. Importantly, this isn’t limited to the famous; the tendency to use ambiguous apologies to navigate difficult situations is a common human behavior.

A Call for Clarity and Improved Interaction

To mitigate the divisive effects of this linguistic imprecision, we must actively seek and promote clarity. This starts with our own communication. When we genuinely mean to admit fault, using less ambiguous phrases like “I apologize” or the even more direct “What I did was wrong” can prevent confusion. We should strive to be mindful of how our words might be interpreted and aim to minimize potential misunderstandings. Equally important is how we interpret and respond to the apologies of others. The common reaction of immediately accusing someone of insincerity or faking an apology, while perhaps intuitively satisfying, is problematic. We cannot know another person’s internal state with absolute certainty, and such accusations often escalate conflict, breeding defensiveness and cycles of hypocrisy. A more constructive approach is to ask clarifying questions. Instead of assuming we know the intent behind an ambiguous “I’m sorry,” we can gently probe for more specific meaning. Questions like “Why are you sorry?”, “Do you admit that what you did was wrong?”, or even “Can you explain why what you did was wrong?” require the speaker to be more explicit. Asking why something was wrong is particularly powerful; it necessitates a demonstration of understanding and is much harder to fake than a simple verbal admission. A refusal to explain or an incoherent explanation can often reveal a lack of genuine belief in wrongdoing far more effectively than a direct accusation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the word “sorry,” burdened by its multiple meanings and often employed with strategic ambiguity, has become a focal point of misunderstanding and division in contemporary culture. The resulting confusion fuels judgmentalism and tribalism, hindering productive discourse and reconciliation. By recognizing the inherent ambiguity of the word and actively seeking clarity—both in our own expressions of remorse and in our interpretation of others’ apologies—we can begin to dismantle the barriers to genuine understanding. Prioritizing clarifying questions over hasty accusations offers a path toward more honest interactions and a less divided society.

This was written by Daniel Lyons.

If you'd like to support him, please consider buying him a coffee so he can create more content like this.